.jpg.rend.hgtvcom.966.386.suffix/1655824578728.jpeg)

I’ll absolutely confess to being something of a swing nerd. When I work on my game with my main coach, Mark Blackburn, I want to see all the data behind what I’m doing and understand what’s happening under the hood. However, the conversations we have on Wednesday of a tournament week are very different than those in a practice session.

When it’s time to play, you need to think about position, not perfection. How do you leave this shot in a spot where you can hit the next one? If you do make a bad swing, how do you absorb that and move on without throwing your round away? That’s much more about mind-set, decision-making and discipline than it is about technique. I’ve learned to be tough on myself for making reckless decisions and letting negativity from a bad shot bleed over—not for failing to execute a swing the way I wanted.

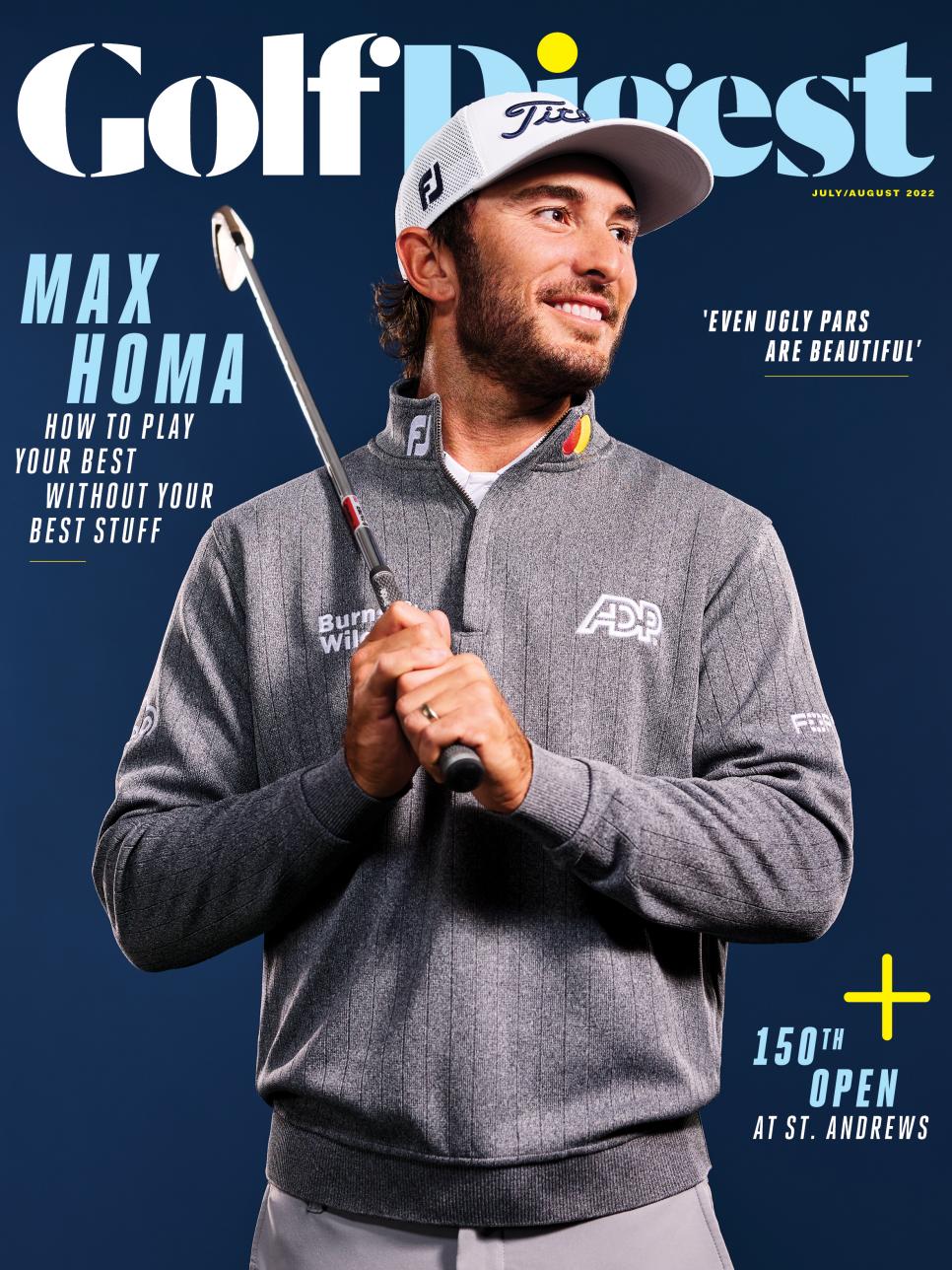

That’s what I’m after in this story—to help you get some of that attitude. I’ll help you play your best when you don’t have your best by taking you through my game from tee to green and showing you how I make decisions and pick shots that reduce risk and release pressure. I want you to have a similar process, so you don’t get trapped in a negative, defensive cycle. Then again, if negative, defensive cycles are your thing, that’s cool, too. You do you. We’ll be over here making good pars. —With Matthew Rudy

DRIVING

DOWNSHIFT TO GET IT IN PLAY

If you’re on a bad run of holes, it’s tempting to try something different off the tee or swing at 140 percent—because, hey, what you’re doing isn’t working.

Instead, you should be tightening your choices under stress, not multiplying them. In those times, I get the physics of the clubs to work for me instead of trying to fight them. My advice is, return to your most reliable option off the tee, even if it’s not the best shot for the hole or you’re giving up distance. Just get it in play.

Normally with my driver, I try to air it out with a cut. But when I’m not hitting it great or accuracy is a must, I’ll go with two other options.

When I need to hit a draw, I’ll use my 3-wood. I move the ball position from in line with my lead shoulder—like I would for a driver— to the right side of the logo on my shirt. I also set up closer to the ball. You can see my arms hanging closer to my body (above, top left). Finally, I close my stance so my toe line is a little right of my target. All of this helps me draw it.

When I can still play a cut driver but have to find the fairway, I tee the ball down. You can’t even see it in this picture (above, bottom left). I then aim at the left edge of the fairway, swing slightly out to in, and embrace the left-to-right curve, finishing with this “held off” look (above, right). The ball doesn’t fly as far, but I also don’t have to send out a search party to find it.

IRON PLAY

SET THE FACE, THEN SIMPLY PIVOT

It’s natural to feel desperate when you can’t find the center of the face with your irons, or you’re spraying the ball all over the place. I’ve been there, and the way out is to pare down as many things from your swing as you can. That means resisting the temptation to try to make the ball curve or adding speed with extra hand action through impact. Instead, start hitting good shots again by getting the clubface in a stronger position and letting your body’s pivot do the work. Let me explain.

If my clubface is skyward at the top of the swing (above, left), it’s in a strong or “closed” position. Then as my arms drop in the downswing, I get the clubface parallel to my spine (above, right). Now it’s way more closed, I bet, than you have it at this point—and the sweet spot on the face stays behind me instead of lurching out toward the target line as I rotate my chest through.

When you get the clubface in this position halfway down, you’ll notice a big difference in how the ball comes off the club. You’ll compress it instead of wiping across it. Then it’s a matter of swinging more from inside the target line to straighten out shots if you’re hitting pulls.

Once you’re striping it and want to start changing trajectory and curve, adjust only one thing: Move the ball slightly forward to hit it higher and fade it, or move it back to hit it lower with more draw. That formula is key to consistency.

WEDGES

QUIET YOUR WRIST ACTION

Keeping with the spirit of limiting choices when your game goes crooked, distance wedges are easier to hit under quieter hand-action conditions. The most forgiving wedge shot comes from a swing with a wider arc and minimal hinging and unhinging of the wrists.

When you’re struggling with these shots, it’s usually because you’re making a steep swing and hitting the ground in inconsistent places. One shot is heavy and 20 yards short, and the next one is clean and 10 yards over the green.

Try a shallower, Steve Stricker method instead. Stay stable and make a backswing with very little wrist set (above). With less set and a wider arc, the attack angle will be much shallower, and the ball comes out lower. You don’t need it to drop from the heavens to stop it because your stability through the shot is going to produce cleaner contact and a lot of spin.

Even if you don’t catch it just right, the shallower attack angle gets the bounce of the club, its backside, sliding on top of the turf, so you still produce a decent shot. Remember, if you’re taking big pelts of sod when you hit these shots, you’re doing it wrong.

SHORT GAME

RELY ON THE CUT SPINNER

On days when you’re off with your driving or ball-striking, you can make things right with your short game. I use this “cut spinner” so much around the greens, it’s almost a default shot now. What is it? It’s a low-trajectory pitch with a high-lofted wedge and an open clubface. When it lands, it hops, then checks up. When you need to get the ball close to the hole on fast greens, it’s a get-out-of-jail-free card—but it does take more practice than the standard technique.

First, set up closer to the ball with the handle vertical and the face slightly open (above). Most of your weight is going to stay on your lead side, and your head should drift slightly toward the target during the backswing. Then, as you swing down and through, pivot around your lead leg, keeping the clubface open. Feel like you’re getting taller through impact and that your hands are following your body’s pivot. The handle of your wedge will point at your left hip after impact. If you hang back, you’ll wreck the shot, hitting it fat or thin.

The great thing about this shot is that the steeper angle of attack caused by swinging with so much weight on your lead foot makes it work from almost any lie where you can get the club on the back of the ball. Just remember: It won’t check as well if you play it from the rough. Allow for some more rollout.

PUTTING

HIT RESET WITH A FOCUS ON CADENCE

Putting slumps get magnified when you don’t understand what’s producing them. I figured out my issues and made my putting dramatically more predictable with the help of Mark and putting coach Phil Kenyon, but I’ll get you back on track. First, my story.

I used to have runs where I’d ram putts in from everywhere, but my success obscured the fact that my lines and speed weren’t always great. When I struggled or was under pressure, I couldn’t rely on my judgment.

Phil taught me the AimPoint system to read greens accurately, so I could be confident I was starting the ball on the right line. Now, way more of my putts look like they have a chance to go in on cold weeks. When I’m hot, like I was at the Wells Fargo this year—where I gained 7.5 strokes on the field in putting—the hole looks huge.

Even if you don’t use a green-reading system, you can still get a clean reset to your putting by paying attention to cadence. Think about your putts in terms of rhythm and timing. A five-footer and 40-footer have strokes with the same beat and timing. The only difference is the 40-foot putt has a longer and faster swing.

Instead of worrying about missing the putt, focusing on cadence also redirects your attention to something positive. When you don’t have your best stuff, the right attitude can do wonders.