A History Of Swing Thoughts

Let me start by saying I'm a mediocre golfer. Not mediocre as in can't-get-the-ball-airborne mediocre. I mean, I'm competent. I can "get it around," as the euphemism goes. I just mean mediocre in the way most of us are mediocre, which is to say there's a healthy disconnect between what I think I should do with a golf ball and what I actually do.

The problem for players of my level is there's really no hope of your swing staying exactly the same. Circumstances change. Consider your best-ever hair day. It was probably a confluence of a number of events. The shampoo/conditioner ratio. Hair length, humidity level. For whatever the reason that day, it all just clicked. (Or so I'm imagining. I don't have much hair anymore.) The point is, as much as you would like to replicate your version of perfection, so much of it is fleeting, and impossible to reconstruct. That's the golf swing. You correct one thing, it invariably surfaces a flaw somewhere else.

Of course there are people who are able to overcome such constraints and make steady progress regardless. As a rule, these people are either A) physically gifted, or B) unemployed.

Otherwise, you have a pattern like mine, a seemingly endless cycle of pushing and pulling, compensating and overcompensating, progressing and regressing.

The Audacity of Hope

Like a lot of golfers, my golf education began with KEEP YOUR EYE ON THE BALL. It was gym class in eighth grade, hitting plastic whiffle balls behind the football field. Mine was not much of a golf family. But I fancied myself an above-average athlete, with plenty of experience with stick-and-ball sports: hockey, baseball, tennis. The act of hitting a ball, at least a whiffle ball in the shadow of the stadium bleachers, came rather naturally, and I felt like I was a decent-enough mimic where I grasped the principles of the swing quite quickly.

I remember one time a few years later when I was working as a pizza-delivery boy, I took a golf club out of the trunk of my car in the pizza shop parking lot and took a couple of practice swings. The guy making pies that night was a short, excitable man named Frank, who immediately rushed out from behind the counter. "Hey," he yelled. "You've got a great swing!" For a moment, I disregarded all the mounting evidence to the contrary -- or that Frank probably wasn't the most discerning critic -- and allowed myself to marinate in the thought. "He's right. I DO have a great swing."

But I didn't. Not in any tangible golf way, at least. Because when the task was actually hitting a real golf ball on a real golf course, the realities of the game started to intercede. My long, loping swing, so fluid in gym class and in pizza shop parking lots, was ill-suited for actually making square contact. This was the early '90s, not quite the Tiger Woods era, but a time when upright, broad-shouldered golfers like Greg Norman and Davis Love III ruled the sport. From a body-type standpoint, this was a reasonable-enough model. I've never been broad, but I've always been on the tall side, with long arms that, in theory, should create width and speed. My thought became HIT DOWN ON THE BALL, just like Norman and Love. But I couldn't do it. It never really worked. Coming in steep required impeccable timing and precision, neither of which I could produce with any regularity. I hit balls fat, or thin, very rarely flush. Through much of high school and then college, when golf became something to do before the bars filled up, I grew accustomed to rounds when I scraped it around in all sorts of undignified ways and was thrilled to break 100.

Wait, try this

A breakthrough came in 1997, inspired not by Tigermania, but rather, Justin Leonard. I know what you're thinking: Justin Leonard? But back then, Justin Leonard was a thing. He won the Open Championship at Troon and then had a chance to win the PGA Championship at Winged Foot. That PGA was the first major I covered as a newspaper reporter, and I remember at some point, hearing a comparison between Leonard's swing and the baseball swing of Mickey Mantle. For some reason, the image clicked. If the steep swing yielded such distressing results for me, then I needed to bring the club more across my body like Leonard -- to be flatter. And flatter I could do. Flatter was not only a baseball swing, but a forehand, or a slapshot.

So my directive became to COME AT IT FLATTER. Specifically I thought of reaching behind me as if to shake someone's hand, then following through to hit the back of the ball. And it worked. The game opened up to me. GOLF! Now it made sense. To that point, I think I was more intrigued by the idea of the game than the game itself -- the setting, the camaraderie, the cliched one shot a round that brings you back. But to hit the ball in the general vicinity of where I wanted it to go on a semi-regular basis, to be able to grind out a score that I'd actually be willing to say out loud, this was life-changing. That sounds dramatic, but it was true. I had bought a single membership to the course in town that enabled me to play unlimited rounds, and I took advantage to the extent that the starter began to look at me with disdain. Don't you have anything better to do?

Ask my boss or my girlfriend (now my wife) or my parents, and of course I did, but I was so clouded by my obsession with golf that it was difficult for me to think of anything else.

My biggest problem was that I just wasn't very long. In fact, I was a bunter, so haunted by the lingering memory of ripping up the sod with my earlier steep downswings that I was reluctant to pull the club back beyond my ears. I just wanted to hit the ball clean. I was six-feet tall, but I liked to crouch as if nature beckoned and I was without the luxury of a toilet. When I played with my brother, he loved to mock how I stuck my ass out with such purpose at address. It was comedy, but the alternative was much darker. I learned to live it.

Eventually came the conclusion that if I was insistent on this flat, abbreviated backswing, I should be sure to compensate the other way. My new mantra was to accentuate the follow-through, or more precisely, THROW YOUR BELT BUCKLE TO THE TARGET.

In theory, this was a positive revelation. On a good day I could get it out there within respectable proximity of my friends. Some days I'd even inch past them. The results were intoxicating. A 7-iron approach! Once in a while, a wedge! Just as I delighted in first learning to catch the ball cleanly, I was seduced by the idea of a second shot that did not involve a long, breathless walk to the green.

So things were moving in an encouraging direction, until suddenly, they were not. I say suddenly, and yet it was probably a gradual regression. Like gaining 20 pounds, or falling out of love. These things don't just happen. All I remember is at some point the ball was jumping off my club and heading . . . left. Adjustments were made -- alignment, tempo, ball position -- and then the ball went . . . even more left.

By this point I had become well-versed in the various ways one can mis-hit a golf ball, and yet this might have been the most demoralizing way of all. I'd call it a hook, but a hook suggests something more benign than what it was, because these balls would just dive left, very often disappearing into some decorative bush that really wasn't intended as part of the field of play.

"Where'd you go?" a playing partner might ask if he looked away for a moment.

"I think I'm in that bush," I'd say.

"That bush?" he'd ask, followed by silence. And then: "No, seriously, where'd you go?"

No one knows me like I know me

Now this might be time for an appropriate question: Why wouldn't I just take a lesson? I certainly aspired to get better, and it was apparent I wasn't getting very far on my own. Both good points. For starters, I was cheap. First, I was single and in an entry-level newspaper job, and then I was married and in a newspaper job, and then before long, there were these two boys at my dinner table. If I was going to spend time and money on golf, I was inclined to do so actually playing.

But that was only partially true. Because if I was convinced a golf pro could put me on the path to better golf, I suspect I would have forked over an irrational amount of money, even if it came at the expense of food and shelter for my kids. (I'm kidding! Mostly.) Thing is, I had taken some lessons, and save for temporary fixes, they only reinforced to me that my circumstances were intensely unique -- that no pro could quite understand how my limbs interacted with one another. It reminded me of when I was a kid and I told my mom I wasn't feeling well and she would ultimately say, "It's probably gas." Every time. It didn't matter if it felt like my throat or my head, and nowhere near my stomach. Perhaps that was when I lost faith in the ability of others to diagnose me properly.

The blessings of indifference

Time passed. Marriage. Those kids. An increasingly demanding career. All elements that comprise a meaningful and productive existence. But if your objective is good golf, it's poison. When my boys were babies and I was enraptured by their every move, the game receded to the periphery, and I didn't really mind. It was like when Tiger Woods was at the height of his dominance and Jack Nicklaus said family was one of the few things that could stand in his way. That was me, except A) I was never any good to begin with, and B) the whole sex-scandal part.

There were isolated outings. My brother's birthday. Some media boondoggle. Inevitably certain parts of my game deteriorated. Putting, once a relative strength, became a mystery. I'd leave one putt six feet short, I'd hammer the next eight feet past. In fact, I had no touch anywhere around the greens, having lost that fleeting, intuitive sense of what a 60-yard shot feels like versus one 10 yards longer.

Otherwise my level was surprisingly passable. My soul-crushing smother hook hadn't exactly been cured, but I was playing so infrequently, it loosened its grip on me. There's an advantage to foggy muscle memory, and one is both your good and bad habits tend to disappear below the surface.

But what really helped? Not caring as much. Or low expectations -- however you want to describe it. The point is, when you stop investing so much in the game, you're less dependent on the return.

I shouldn't oversell it. A 91 is still a 91, but remember, this was a time when I was barely playing, when I was content to treat golf like some light-beer commercial, a respite from the madness of everyday life. My swing thought was SWING SMOOTH, which epitomized my happy-to-be-here insouciance. My relationship with golf had reached a pleasant, amicable level, like a divorced couple who realize they can get along fine as long as they don't have to live together.

A drunk in a brewery

Then I got hired at Golf Digest, a dream job by many measures, but one that also squashed any hope of keeping the game at arm's length.

The problem with working at Golf Digest is the game has a way of seeping into your pores. The walls lined by pictures of classic golf swings. The hundreds of new clubs just lying around, inviting you to pick them up. There's even an indoor putting green where we have money putting contests on idle winter afternoons. Eventually there's spring, and an invitation for Friday golf. And then the inevitable, "That was fun. Let's do this again next Friday." And pretty soon you're hunched over your laptop in the dark studying a repeating slow-motion video of your takeaway.

Here is where my swing thoughts went into overdrive, because Golf Digest is nothing if not a high-volume dispensary of swing thoughts. Follow the recommended dosage, and they can be enlightening, but I gobbled them up in unhealthy batches. From Hank Haney I endeavored to weaken my grip ("HIDE YOUR LEFT THUMB"). From Jim McLean, I straightened my takeaway ("POINT THE SHAFT TOWARD THE TARGET" ). Phil Mickelson advised on quieting my legs (""KEEP YOUR HEEL ON THE GROUND"). For a while I toyed with Stack & Tilt, a fairly radical swing methodology in which you load all your weight onto your left side and angle your front shoulder downward ("TURN YOUR BODY LIKE ON AN AXIS"). It worked for a little while, until, like most swing changes, it didn't. Or maybe I lost interest. I forget.

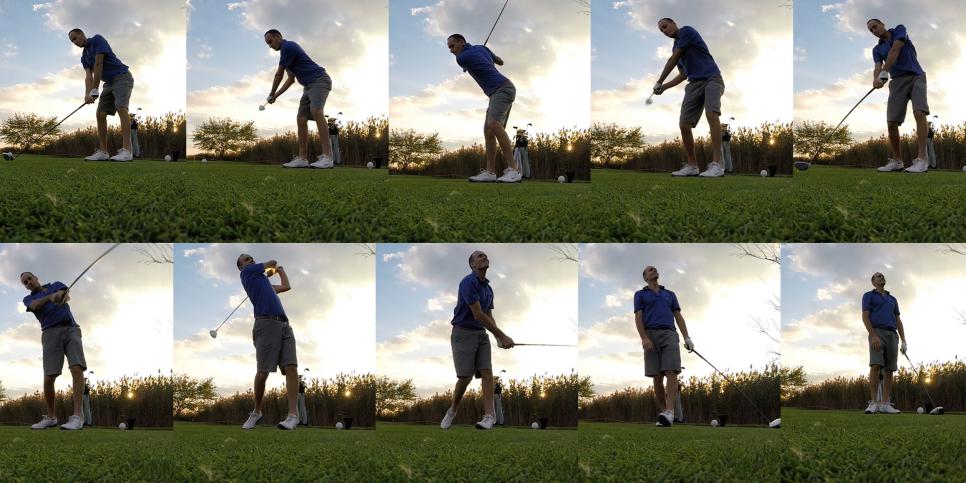

Compared with my peers I had gathered an exhaustive knowledge of the golf swing, but on a practical level, it has mostly worked against me. Instead, what sustains me -- or perpetuates my misery depending on how you look at it -- is an almost absurd level of optimism. For someone so battle-scarred, I continue to convince myself good golf is tantalizingly close. Even now as I write this, buoyed by six holes of stress-free golf at dusk a few days ago, I think, "Sure, I USED to be that way, but I'm better than that now."

Am I really? Probably not. But if only to stave off the notion that it's been a tragic waste of time and energy, I cling to any thread of hope I can. I think about two years ago, in the annual company golf tournament, when the final outcome hinged on my match, and my 7-year-old son served as my caddie. That day had been a familiar stew of good and bad, chunks and lip-outs, interspersed with occasional flashes of skill. By the final hole, all the other matches were over, so the entire editorial staff filtered out to watch us, drinks in hand, snark already flying at a rapid clip. It was 175 yards, over water, and I remember thinking it would be a victory if I did not miss the ball outright and have the hybrid fly out of my hands, striking our Editor-in-Chief dead. (Swing thought: "DON'T KILL YOUR BOSS.") Instead, I took the club back slowly (next swing thought: "TEMPO"), made square contact and watched the ball soar toward the green, eventually settling 30 feet left of the pin. Moments later I would complete a difficult two-putt, we ended up winning the whole thing, and my son jumped into my arms.

"I was so nervous," he said as he hugged me. He didn't say anything about everything that could have gone wrong in that moment, although having watched the first 17 holes, he surely entertained it. There would be plenty of time for us to dwell on all the misfortune golf can heap upon you. For a brief moment, we enjoyed the taste of something actually going right.